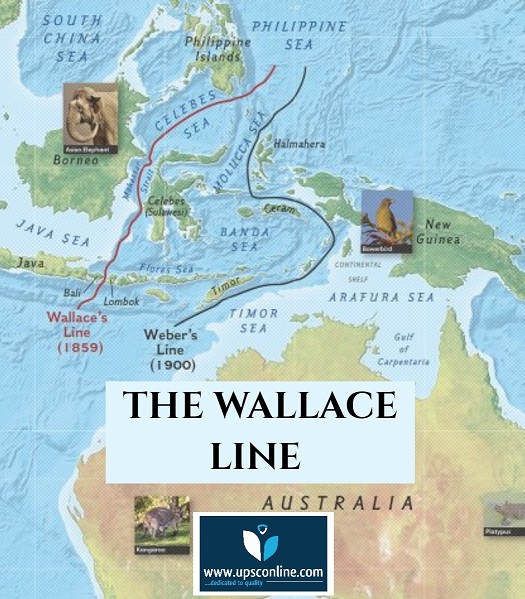

The Wallace Line is an imaginary line that intersects the Lombok Strait between the Indonesian islands of Bali and Lombok to the south, and extends north through the Makassar Strait between Kalimantan (Borneo) and Sulawesi.

Wallace’s Line is not a static boundary—it has shifted over time due to the interplay of geological transformations and climate change. As sea levels fluctuate, land bridges appeared and disappeared, offering brief windows for species migration. The two regions are different continental plates that have been moving independently — the Asian and Australian plates

On the shoreline of Bali and its eastern part. Across the water channel, there is island of Lombok. There is a narrow 21-mile-wide stretch of ocean, known as the Lombok Strait, separates these two islands. In 1858, British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace wrote Charles Darwin a letter , from the Malay Archipelago.

He had spent years documenting species across the region. The natural world was not a seamless blend of species, but a patchwork divided by invisible barriers.

One of those barriers, the one running through the Lombok Strait was the most striking of all known as Wallace’s Line. Before the exploration of Wallace, in the 1850s, the general belief was that, species were static & distributed based on environmental conditions, with little or no consideration for Earth’s historical processes.

Wallace’s meticulous documentation of species distributions ended this assumption. He observed that, despite their proximity and environmental similarity, the islands of Bali and Lombok had vastly different fauna.

Wallace identified the 250m depth of the Lombok Strait as the single most compelling explanation for the differences between Asian and Australian animals. It caused various species to remain isolated from each other on opposite sides of the Lombok Strait through centuries of migrations and evolution.

The Sunda Shelf is a continental shelf that incorporates Borneo, Java and Sumatra, and is joined to peninsular Malaysia and the mainland nations of Vietnam and Thailand.

Bali is joined to the shelf but Lombok is separated from the shelf by the comparatively deep Lombok Strait. The Sahul Shelf in the east joins Australia and New Guinea. Between the Sahul Shelf and the Sunda Shelf is a constellation of islands and seas known as Wallacea.

On the west side of the Wallace Line in Borneo, Sumatra and Java— there is a presence of creatures with deep Asian roots e.g. tigers, rhinoceroses, elephants and primates.

On the eastern side into the Lesser Sunda Islands, Sulawesi and New Guinea, the creatures belonging to Australian species like marsupials, such as tree possums climb through forests, cockatoos and lorikeets speckle the skies and egg-laying mammals like echidnas.

REASONS OF THIS DIVISION

The secret lies beneath the ocean’s surface. During the recent Ice Ages, when sea levels fell, land bridges connected many Southeast Asian islands to the mainland, allowing species to migrate freely.

But the deep waters of the Lombok Strait never dried up. It remained a formidable barrier, preventing species from crossing, leaving two distinct evolutionary worlds to develop independently.

CHANGING COURSE OF EVOLUTION

A highly adaptable primate like Macaca fascicularis, found on the west of Wallace’s Line, it adopted an arboreal lifestyle by developing a long tail. They mark their presence across the forests from Thailand to Borneo, it has also successfully integrated into urban environments.

On the eastern side of of Wallace’s Line in Sulawesi, there is a species of booted macaque, or Macaca ochreata, developed a more robust body and a shorter tail, adaptations suited to the island’s dense forests and differing food sources.

This geographical isolation lead to change in their behaviour. Macaca fascicularis , a crab eating , macaque, living on the west side of Wallace line , are opportunistic and often raid crops and human settlements. are opportunistic and often raid crops and human settlements.

A nocturnal bird found in Southeast Asia, known as Sunda frogmouth (Batrachostomus cornutus) belongs to an ancient lineage mostly confined to the Sunda region. This species shown phenomenal adaptation for tropical forest , especially its camouflage.

However, on the Australian side of Wallace’s Line, the tawny frogmouth (Podargus strigoides) and its relatives have evolved separately, adapting to comparatively drier ecosystem.

This divergent evolution dates back to the Oligocene, period, means 30-40 million years ago, considered as the oldest known vertebrate divergences across Wallace’s Line.

This long-standing separation or geographical isolation suggests that island arcs and continental plate movement land may have provided a land corridor for dispersal.

Animals on the western side of Wallace Line if crosses the Wallace line and enters the eastern side, they may struggle for their existence due to change in the climate & vegetation. However some animals may survive if they cross the Wallace line.

If protected from survival odds, like competitors, predators, or disease—they may successfully colonize the new habitat & ecosystem, the way invasive species are doing. Some species of bats, such as flying foxes, are found on both sides of the Wallace Line, as they can travel long distances in search of food and roosting sites.

THE HUMAN WALLACE LINE

Some anthropologists travelled to east Nusa Tenggara (the Timor Archipelago, including the islands of Timor, Flores and Sumba), where Alfred Russel Wallace had drawn a dividing line between the races of the east and the west of the archipelago.

These medically trained anthropologists aimed to find out if the Wallace Line could be more precisely defined with measurements of the human body. However anthropologists failed to find definite markers to quantify the difference between Malay and Papuan/Melanesian.

This, however, did not diminish the conceptual power of the Wallace Line, as the idea of a boundary between Malays and Papuans was taken up in the political arena during the West New Guinea dispute and was employed as a political tool.

The structuring concept for the human diversity in this region was the difference between people with frizzy hair and darker skins in the east and light brown people with straight hair on the western islands. From the 1880s onwards, physical anthropologists were eager to measure the physical differences between Malays and Papuans

The human Wallace Line became salient, especially during the West New Guinea dispute, and was employed as a political tool by all parties involved to further their goals. The map was considered as, a visual tool to abstract knowledge and to circulate it. It became a tool Not only for mapmakers and geographers but also for biologists, ethnologists and medical experts.

Jane Camerini argues that, In racial science, maps simplified diversity and emphasised racial difference. Johann Reinhold and Georg Forster, travelled with James Cook have observed ‘two great varieties’, one ‘more fair, well limbed athletic, of a fine size and a kind benevolent temper; the other blacker, the hair just beginning to become woolly and crisp, the body more slender and low, and their temper, if possible more brisk, though somewhat mistrustful

In the nineteenth century, John Crawfurd and George Windsor Earl confirmed this division. But French anthropologists Armand de Quatrefages and Ernest Hamy, opined that, Wallace ignored, the presence of so-called Negritos, groups of people of small stature who were found on each side of Wallace’s anthropological line. The anthropological practice of drawing lines was a forceful tool to establish racial categories.

The imagined boundary between Malays and Papuans has been a consistent feature of our conceptions of Southeast Asia, even though the line has moved on the map over time. Anthropometrics hoped to find the right markers that could be used to define the difference between Malays and Papuans quantitatively, but it turned out to be impossible to link characteristics such as the cephalic index to one of the two groups.

0 Comments